What if you needed an important contract signed or an approval for a critical financial transaction by Friday? Would operations grind to a halt, or would someone you trust step in seamlessly? That’s exactly why you need a power of attorney letter. It documents the legal architecture behind it, knowing which type of delegation protects you.

Recent surveys reveal that 55% of Americans lack any estate planning documents, including powers of attorney. For businesses, the stakes are even higher: unclear agent authority remains one of the most common sources of invalid transactions, delayed closings, and regulatory failures.

This guide walks you through everything: from selecting the right POA structure to understanding fiduciary obligations, state-specific execution requirements, and how modern contract lifecycle management systems are transforming POA oversight from reactive firefighting into strategic governance.

What exactly is a power of attorney (POA) letter?

A power of attorney letter is a legal document where one person (the principal or grantor) authorizes another person (the agent or attorney-in-fact) to act on their behalf in legal, financial, or medical matters. Think of it as a controlled delegation: you’re handing someone the keys to specific decisions, but you’re also defining exactly which doors they can unlock.

The document itself outlines the scope of authority, duration, and specific powers granted. It can be as narrow as “approve this single real estate transaction” or as broad as “manage all my financial affairs indefinitely.”

Approximately 16% of older adults worldwide experience some form of elder abuse, including elder family financial exploitation (EFFE), the unlawful transfer and theft of funds and property perpetrated by a family member. Power of Attorney arrangements, when constructed and executed properly, can be critical tools for protecting against such exploitation.

Let’s see who’s who here:

Principal (or Grantor): The person granting the authority. This is you if you’re creating the POA.

Agent (or Attorney-in-Fact: The person authorized to act on behalf of the principal. Despite the name, they don’t need to be a lawyer; they just need your trust and legal capacity.

Attorney-in-Fact vs. Attorney-at-Law: An attorney in fact is granted power of attorney to act on someone’s behalf, but cannot practice law unless also licensed. Your college roommate can be your attorney-in-fact; only a licensed legal professional can be your attorney-at-law.

In corporate settings, you’re not just protecting one individual. You’re safeguarding organizational assets, maintaining regulatory compliance, and ensuring that authorized signatories have clear, documented parameters. Every POA should answer: *Who can do what? Under which circumstances? Until when?*

Why “general” vs. “limited” scope changes your risk profile

Scope determines exposure. A general POA grants sweeping authority across all financial and legal matters. A limited (or special) POA restricts the agent to specific actions like selling one property, managing a single account, or representing the principal in a particular transaction.

General POA:

- Broad authority over finances, legal matters, and business operations

- Higher risk if the agent acts beyond the principal ‘ s wishes

- Typically used when the principal needs comprehensive, ongoing representation

Limited POA:

- Narrow, transaction-specific authority

- Lower risk profile due to defined boundaries

- Common in real estate closings, tax filings, and business deals

For organizations, limited POAs are almost always the safer choice. They create what we call ‘minimum necessary authority’ enough power to get the job done, not enough to create runaway liability.

Power of Attorney Letter free template here

The core types: Which POA letter matches your needs?

The type of POA you choose determines when the authority kicks in, how long it lasts, and whether it survives incapacity.

Durable vs. non-durable: Planning for incapacity

A durable power of attorney remains in effect even if the principal becomes mentally or physically incapacitated. A non-durable POA terminates the moment the principal can no longer make decisions.

Durable POA:

- Survives incapacity (the whole point)

- Must include specific “durability language” like: “This power of attorney shall not be affected by subsequent disability or incapacity of the principal.”

- Essential for long-term planning, elder care, and business continuity

Non-Durable POA:

- Ends if the principal becomes incapacitated

- Often used for temporary situations (travel, short-term illness)

- Not suitable for estate or succession planning

If you’re building operating agreements for an LLC or planning business continuity, durable POAs are non-negotiable. You need authority that persists through health crises, not documents that evaporate precisely when you need them most.

Springing POAs: The “only if” clause for peace of mind

A springing power of attorney doesn’t activate immediately. Instead, it “springs” into effect only when a specific triggering event occurs, typically the principal’s incapacity.

How it works:

- Document specifies the triggering condition (e.g., “two physicians certify that I am unable to manage my affairs”)

- The agent has no authority until that condition is met

- Offers psychological comfort: “I’m granting power, but only if I truly can’t act myself.”

The trade-off:

- Delays action (agent must prove the trigger occurred)

- Third parties (banks, title companies) may require proof of incapacity before honoring the POA.

- Can create friction during emergencies

For compliance teams managing POA portfolios, springing provisions add monitoring complexity. You track expiration dates, trigger events, physician certifications, and activation timelines. This is where automated contract management software becomes indispensable.

Medical and financial delegation

Financial POA:

- Authority over bank accounts, investments, property transactions, and tax filings

- Can be general or limited in scope

- Subject to fiduciary duty(act in the principal ‘ s best financial interest)

Medical POA (Healthcare Proxy):

- Authority to make healthcare decisions when the principal cannot

- Often paired with advance directives or living wills

- Covers treatment decisions, facility choices, and end-of-life care

Organizations rarely deal with medical POAs, but understanding the distinction matters. If an employee submits a POA to handle company matters, verify its financial scope. A medical POA grants zero authority over business transactions.

Anatomy of a solid power of attorney letter

Not all POA documents hold up under scrutiny. A well-drafted POA balances clarity, legal compliance, and operational usability.

Step 1: Defining the scope of authority (and the limits)

Ambiguity is the enemy. Your POA should explicitly list what the agent *can* do and, equally important, what they *cannot* do.

Powers typically granted:

- Banking and financial transactions

- Real estate purchases and sales

- Contract execution

- Tax filings and IRS representation

- Business operations and management

- Legal proceedings(within defined parameters)

Common limitations to include:

- Restrictions on gifting assets

- Prohibitions on changing beneficiary designations

- Limits on borrowing against estate assets

- Requirements for co-signature on transactions above a certain threshold

Think of it like hold harmless agreements or non-compete clauses; the magic is in the specificity. Vague authority creates litigation. Precise boundaries create protection.

State-specific execution: Notaries, witnesses, and legal dignity

Here’s where POA documents often fail: improper execution.

State laws vary significantly. Some states require notarization for all POAs (e.g., Florida, New York), while others allow witnesses instead of notarization (e.g., California, Illinois).

Common requirements by state:

- Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, North Carolina, Utah: Require both two witnesses AND a notary

- Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California: Require either two witnesses OR a notary

- New Jersey, New York: Mandate notarization

Even where not required, notarization strengthens the POA’s legal validity and helps prevent fraud. Banks and title companies routinely reject non-notarized POAs, even in states where they’re technically valid.

Pro tip for compliance teams: Build a notarization requirement into all POA templates, regardless of state law. The $20 notary fee is trivial compared to the cost of a rejected transaction or contested authority.

Compliance with EFTA, Regulation E, and others

If your POA grants authority over electronic fund transfers, you’re now in the regulatory crosshairs.

The Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA) and Regulation E create a consumer-friendly regulatory regime that imposes significant servicing obligations on financial institutions, mandates prompt investigation and resolution of consumer disputes, and limits consumer liability for unauthorized transfers.

Key compliance considerations:

- Regulation E governs electronic transfers from consumer accounts(debit cards, ACH, wire transfers)

- Between June 2022 and June 2023, financial institutions filed 155,415 reports related to elder financial exploitation associated with more than$27 billion in reported suspicious activity.

- POA documents should explicitly reference electronic fund transfer authority

- Agent actions under a POA may trigger EFTA disclosure and error resolution obligations.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2024, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center recorded $4.885 billion in losses from 147,127 elder fraud complaints, a 46% increase from 2023. Much of this exploitation occurs through POA abuse in electronic banking.

For organizations, this means your pre-contract agreements and POA templates must include EFTA-compliant language if they touch electronic fund transfers.

Managing POA risk at scale for businesses

Here’s where individual estate planning meets organizational governance. If your company handles multiple POA letters from executives authorizing transaction authority to vendors submitting delegation documents, manual tracking becomes a ticking time bomb.

Quick reference guide: Types of power of attorney

| Type | Scope | Duration | Survives Incapacity? |

| General | Broad authority | Until revoked/death | No (unless durable) |

| Limited/Special | Specific transactions | Defined period or transaction completion | No |

| Durable | Broad or specific | Until revoked/death | Yes |

| Springing | Broad or specific | Activates on the trigger event | Yes (typically) |

| Medical/Healthcare | Healthcare decisions only | Until revoked/death | Yes (typically) |

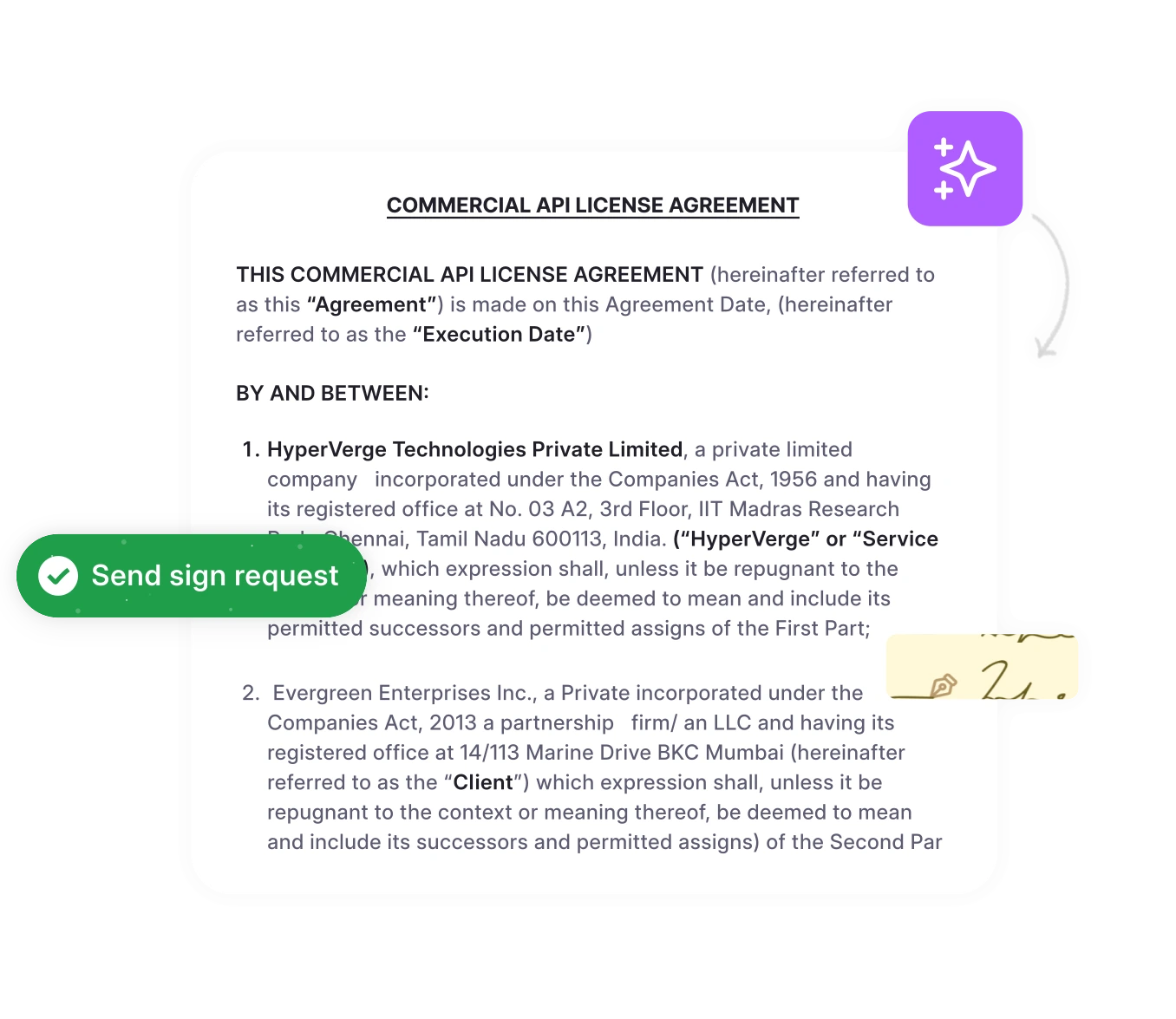

Stop manually tracking expiration dates.

HyperStart alerts you 90, 60, and 30 days before a POA or contract expires, keeping your sanity intact.

Book a DemoWhy manual tracking of POA letters is a liability

Think about what happens when a POA expires, and nobody notices:

- Invalid transactions: Contracts signed by agents without authority are voidable

- Regulatory exposure: Regulators view POA failures as internal control weaknesses

- Financial loss: Deals fall through, closings get delayed, litigation ensues

- Reputational damage: Banks and partners lose confidence in your due diligence

According to independent research, automating contract management speeds up sales negotiation cycles by 50%, cuts inaccurate payments by 75 to 90%, and cuts operating and processing costs related to contract management by 10-30%.

Yet most legal teams still track POA documents in shared drives and Excel spreadsheets. That worked when you had five POAs. It fails catastrophically at fifty.

Using CLM to monitor expiration and “springing” triggers

Modern contract lifecycle management platforms transform POA oversight from reactive to predictive.

What automated CLM enables:

- Expiration tracking: System alerts 90, 60, and 30 days before POA expiration

- Trigger monitoring: Track springing POA activation events(incapacity certifications, triggering dates)

- Authority verification: Instantly confirm whether a specific agent has current authority for a proposed transaction

- Audit trails: Complete history of POA creation, modification, usage, and revocation

- Compliance reporting: Demonstrate to auditors that you have systematic POA oversight

Imagine your company receives a contract signed by an agent under a POA. Instead of manually digging through files to verify authority, your CLM system instantly:

- Confirms the POA exists and is current

- Verifies the agent’s identity matches the POA

- Checks that the transaction falls within the POA’s scope of authority

- Flags any upcoming expiration dates

Strengthening POA oversight: Practical safeguards advisors should implement

A power of attorney concentrates immense authority in a single individual at moments of heightened vulnerability. To reduce the risk of misuse, intentional or accidental, organizations and advisors should move beyond document drafting and implement structural oversight mechanisms.

1. Team Collaboration: Attorney, CPA, and Wealth Manager Reviews

In practice, it looks like a coordinated advisory team that conducts annual or event-driven reviews of the POA and the principal’s financial activity. Each professional brings a different lens:

- Attorney: Legal authority, scope compliance, fiduciary obligations

- CPA: Tax reporting consistency, unusual transfers, income anomalies

- Wealth Manager: Portfolio activity, withdrawals, beneficiary alignment

Financial abuse often occurs incrementally. No single advisor sees the full picture, but collective oversight creates pattern recognition.

This approach mirrors the “three lines of defense” model used in regulated industries: legal authority, financial verification, and operational oversight working together.

2. Consolidated Assets to Reduce Complexity

Advisors encourage principals to reduce the number of financial institutions and account types where possible, consolidating assets under fewer custodians with robust controls. Fragmented assets create blind spots because

- More accounts = less visibility

- Smaller, scattered transactions evade detection.

- Multiple institutions apply inconsistent POA standards.

Complexity disproportionately benefits bad actors. Simplification increases transparency, auditability, and accountability. Asset consolidation is not about convenience—it’s about control architecture.

3. Duplicate Statements Sent to a Trusted Monitor

Account statements are automatically copied to a third party, such as another family member, professional fiduciary, CPA, or trust officer who does not have transactional authority.

This creates passive oversight without operational friction. The agent retains authority, but knows activity is visible.

Best-practice safeguards

- Monitor receives statements only(no access to transact)

- Scope and role documented in writing

- Clear escalation process for concerns

Transparency changes behavior. Oversight does not imply distrust—it enforces discipline.

4. Joint Agents to Reduce Unilateral Power

The POA appoints co-agents, requiring either:

- Joint approval for major actions, or

- Division of authority(e. g ., one handles banking, another investments)

Single-agent POAs concentrate power. Joint agents introduce internal checks and balances, reducing the likelihood of abuse or error.

Trade-offs

- Slower decision-making

- Potential disagreements between agents

When it works best

- Large estates

- Blended families

- High-risk principals(cognitive decline, prior family conflict)

This mirrors dual-signatory controls used in corporate finance for high-value transactions.

5. Agent Monitors or Formal Reporting Obligations

The POA includes explicit reporting requirements, such as:

- Quarterly financial summaries

- Annual accounting to a named individual or professional

- Record-keeping obligations (receipts, logs, explanations)

In some cases, a formal agent monitor (often a lawyer or fiduciary) is appointed with review, not decision-making authority. Misuse often goes undetected because agents are not required to explain their actions. Reporting forces intentionality and documentation.

Clear reporting duties strengthen legal remedies if misconduct occurs. Accountability is not punitive; it is preventive. Reporting obligations convert informal trust into structured fiduciary responsibility.

Best practices: How to write and revoke your POA

Creating an effective POA isn’t rocket science, but it does require methodical attention to detail.

Step-by-step: From selecting an agent to final execution

Step 1: Choose your agent carefully

Look for someone who is:

- Trustworthy and financially responsible

- Organized and capable of record-keeping

- Available and willing to serve

- Free from conflicts of interest

Step 2: Determine the type and scope

Ask yourself:

- What powers do I need to grant?

- Should authority be immediate or springing?

- Do I need durability (survival through incapacity)?

- Are there specific limitations or restrictions?

Step 3: Draft the document

Options include:

- State-specific statutory forms (available from state bar associations)

- Attorney-drafted custom documents

- Reputable online legal services

Step 4: Execute properly

- Sign in the presence of required witnesses and/or notary

- Verify you’re meeting your state’s specific requirements

- Keep the original in a secure but accessible location

- Provide copies to the agent, bank, and financial institutions

Step 5: Communicate and monitor

- Explain the POA’s scope and limitations to your agent

- Review periodically (at least annually)

- Update when circumstances change (marriage, divorce, moves, business changes)

When does the power end? Understanding revocation and automatic termination

Automatic termination occurs upon:

- Death of the principal (immediately and universally)

- Expiration date (if specified in the document)

- Completion of the specific purpose (for limited POAs)

- Principal’s incapacity (for non-durable POAs only)

Revocation requires:

- Written notice to the agent

- Notification to all third parties who may have relied on the POA (banks, title companies, business partners)

- Retrieval and destruction of original documents (best practice)

- State-specific filing if the POA was recorded with county records

In closing

A Power of Attorney should not operate in isolation. The safest POAs function within a governance ecosystem, one that combines legal precision, financial visibility, and human oversight.

Advisors who treat POAs as living governance tools, rather than static documents, significantly reduce risk while preserving dignity and autonomy for the principal.

Frequently asked questions

- the agent,

- all financial institutions that have a copy,

- any other parties who relied on the POA. If the original was recorded with county records, file the revocation there, too.

- The principal dies,

- The principal revokes it,

- The specified expiration date arrives,

- The purpose is accomplished (for limited POAs), or

- The principal becomes incapacitated (for non-durable POAs only).